Students and faculty gathered in late August to meet and discuss their summer’s archaeological research work.

The talk was hosted by the Departments of Anthropology and Middle Eastern and Ancient Mediterranean Studies. Attendees introduced themselves before some students and professors gave formal presentations on their summer research experience.

Students of various academic disciplines participated in excavation work around the world, from the Mediterranean to Central and South America. While Binghamton University does not offer an undergraduate archaeology major, students can take several archaeology classes or pursue a minor in archaeology, according to Hilary Becker, associate professor and undergraduate director of Middle Eastern and Ancient Mediterranean Studies.

“Anyone can participate in an archaeological excavation,” Becker wrote in a statement to Pipe Dream. “No specific skills are required and no coursework is usually expected — skills are learned on site while you are doing them. And in hand, you have the experience of the interaction with the material culture in situ, and the opportunity to see materials that may have not been handled for centuries.”

Bailey Raab, a second-year Ph.D. student studying anthropology, worked at several dig sites over the summer. She excavated and taught undergraduate students at the Turpin site located near Cincinnati, Ohio. Her master’s thesis analyzed samples from the location, which contains remnants of a village occupied by the Fort Ancient culture around 1,000 years ago.

Raab also traveled to Peru to work at two locations — Cerro Sulcha, a northern site that holds several pre-Peruvian architectural structures, and Achomani, a hilltop site in the south.

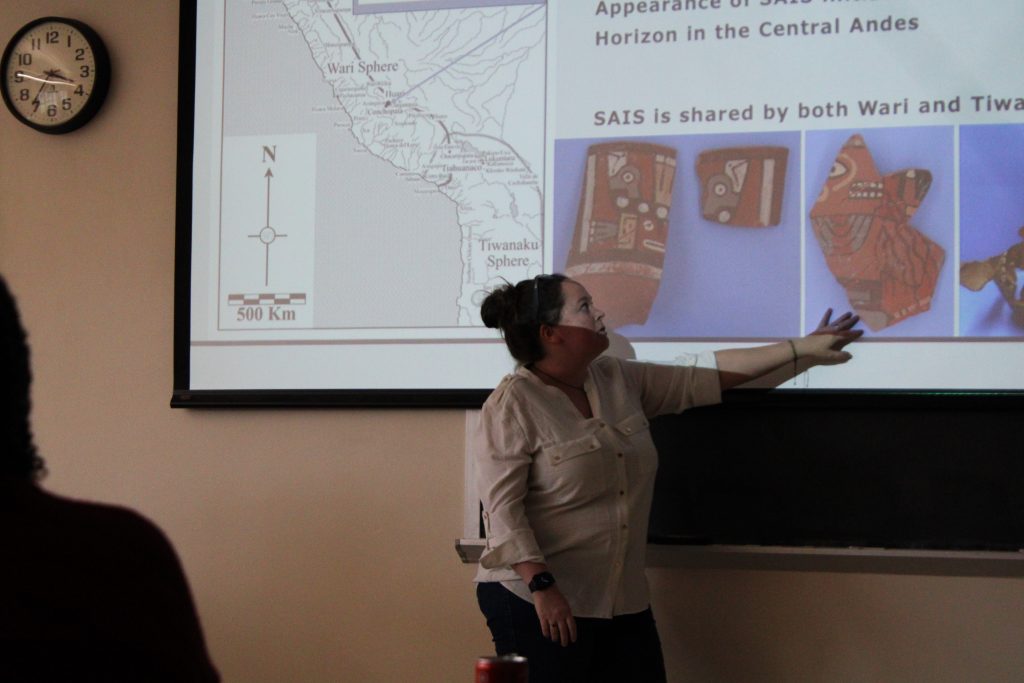

Brittany Fullen, a Ph.D. student studying anthropology, received a Fulbright scholarship and also researched in Peru. She studies the cultural art of the Wari people who lived between the Andes Mountains and the Pacific coast from around 450 to 1000 C.E. Fullen passed around excavated pieces of ornate pottery whose designs were used by both the Wari and Tiwanaku civilizations, which thrived around the banks of Lake Titicaca in modern day Peru and western Bolivia.

BrieAnna Langlie, an associate professor of anthropology, researched in Peru’s Colca Valley and excavated stone and ceramic artifacts estimated to be about 600 to 1,000 years old.

In the lush Central American rainforests of Belize, Liliana Cheek, a first-year graduate student studying anthropology, conducted research with David Mixter, an archaeologist and assistant professor of environmental studies. Mixter runs the Actuncan Excavation in western Belize, working at the site for over 15 years.

Students and experienced staff excavated various parts of an ancient Mayan settlement over the summer. Cheek’s research focused on exploring the pyramid complex as a ritual space. Mixter focused on how water would have been distributed from man-made reservoirs to the local population (11) (17:50, 16:14).

Others spent the summer at sites in Europe. Zach Powell, a senior majoring in chemistry, travelled to southern Italy and worked at Pompeii, an Ancient Roman city destroyed after the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 C.E. Powell went with students from the Casa della Regina Carolina Project, led by Cornell University to examine “relationships between domestic material culture, social performance, and historical change” at a large house in Pompeii.

Powell cleaned samples and analyzed the chemical composition of pigments on excavated materials.

“Archaeology is absolutely not just for archaeologists,” Powell said. “It takes a whole variety of experience and skills to help pull everything together and to help analyze what’s actually going on on-site.”

Becker also conducted research at the site, using various techniques to identify what color pigments were used on the walls by isolating any chemical elements present. She was able to determine that a wax coating was applied to protect the walls sometime in the 19th century because of the sulfur present.

Jesse Lynch, a junior majoring in ancient Mediterranean studies, studied an ancient Roman bath complex with a field school at Cosa, a Roman settlement in southern Tuscany. He was awarded the Saul and Ruth Levin Educational Enrichment Grant from the Department of Middle Eastern and Ancient Mediterranean Studies to help cover expenses.

In France, Emile Rebillard, a junior majoring in medieval and early modern studies and mathematical sciences, helped excavate and survey a Roman burial site near the Pyrenees Mountains.

Becker believes that archaeology is valuable to the wider public because it is a discipline that explores how humans relate to the world around them.

“Archaeologists, regardless of their temporal, cultural, or geographic focus, are committed to the careful documentation of past peoples,” she wrote. “In so doing, their goal is not only to document as carefully as they can what it is that people’s experience (what they made, what they ate, what they believed), but also to apply this documented human experience to what it is to be a human being.”