When J. Hoberman wanted to go to the 1968 New York Film Festival (NYFF), he realized that the best way was to go as a magazine writer. The only trouble was, he wasn’t a magazine writer; he was just a junior at Harpur College.

But that didn’t stop him. Hoberman told the festival that he was a writer for “‘Harpur Film Journal’ or some such,” as he recalled years later. And to his surprise, the ruse worked and the festival gave him press credentials.

“I cut all my classes for the first several weeks, because the festival was in September,” Hoberman said. “I was at the film festival every day.” He ended up writing a 10-page report, which he distributed to the Harpur Film Society.

In its own weird way, that document began Hoberman’s path to becoming the most influential film critic alive.

In addition to his 11 books, he wrote film criticism for The Village Voice for nearly 30 years, and now frequently writes about movies for the New York Times, Artforum, The Nation, Tablet and The New York Review of Books. He’s taught film at Harvard, New York University and Cooper Union. In a list of the best movie critics of all time, Complex listed him at number five, writing, “Simply put, there’s no greater living film essayist than James Lewis Hoberman.”

But before all that, Hoberman got his film education at Binghamton University. He arrived in the fall of 1966, chasing a high school girlfriend, and began as an English major, but switched to cinema under the sway of Larry Gottheim and Ken Jacobs.

Before founding the cinema department in 1970, Gottheim taught cinema courses through the English department and was also the faculty adviser to the Harpur Film Society. (Hoberman never actually took a class with Gottheim.) In 1969, Gottheim brought Ken Jacobs to BU to give guest seminars for a week, and he was so popular that students petitioned to hire him as a professor. The administration relented — despite Jacobs’ lack of a high school diploma — and he began teaching in the fall.

“I took all my remaining courses with him,” Hoberman said, and switched his major from English to cinema.

Today’s cinema department continues Jacobs’ tradition of non-narrative cinema. He’s arguably the most acclaimed experimental filmmaker alive. The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), which has hosted several retrospectives of his work, describes his work as “the aesthetic, social, and physical critique of projected images.”

Jacobs appointed Hoberman as his projectionist. At the time, the professor was known for “Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son,” made in 1969. Still considered a landmark work of experimental cinema (it was admitted to the National Film Registry in 2007), it’s an examination of a piece of footage he found from 1905, refilmed and recontextualized into a feature-length movie.

“What he did was he ran it backwards, he focused in on certain details,” Hoberman said. “He performs all these exercises on the film. So being his projectionist was very stressful.”

Jacobs’ views on cinema changed the way Hoberman saw film. Movies weren’t just self-contained stories made of light and shot on celluloid — they were objects, artifacts and social constructs that told something about the world from which they were made. By examining a film, one examines the series of events and situations that led to its creation. In a New York Times essay about Jacobs on the occasion of his 80th birthday, Hoberman wrote, “I had never encountered a teacher who could talk so passionately about art, spontaneously integrating political views and childhood recollections.”

In the classroom, Jacobs emphasized avant-garde films (“We took them apart, like you might take apart a watch,” Hoberman said), studying Griffith, the Soviet directors and films rented from MoMA. But he also screened Hollywood talkies from the ‘30s and ‘40s, old Yiddish films and talked about movies playing in theaters at the time.

Growing up in Queens, Hoberman always thought he was destined for Queens College. But in his senior year of high school, the opportunity to go to BU presented itself. In 1966, the Regents Exam doubled as an admissions exam to the state university.

“If you got above a certain mark on the Regents, you were not only admitted, but you got a scholarship,” Hoberman said. “It was a fantastic deal. I paid more for day care for my kids than I paid for my entire college education.”

At first, Hoberman lived in Broome Hall in Newing College, but found off campus cheaper.

“I lived on campus for not even a full semester,” Hoberman said. “I knew some people who were upperclassmen, and they needed a roommate, and I just got permission to move off campus.” Like many students, he lived “in various sketchy parts” of Binghamton, but moved to the West Side, which “was kind of nice.”

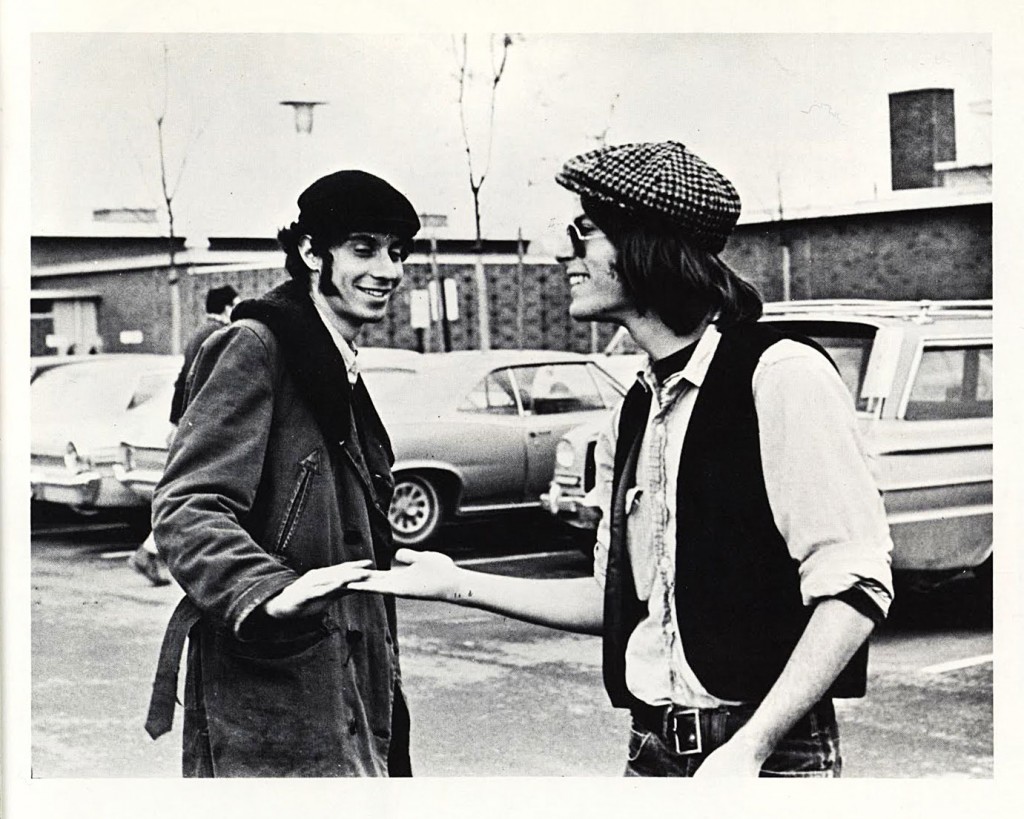

A year before Hoberman enrolled at Harpur College, a young Art Spiegelman did. The two met on campus and struck up a friendship, one that lasts to this day. Young Spiegelman was also a disciple of Jacobs’; he left Harpur College in 1968, but stayed in the Binghamton area and continued going to his classes.

“In those days, any college town would be full of people who would drop out and stayed around, or other people who just sort of gravitated there,” Hoberman said. “He had a very well-developed sense of aesthetic as it related to comics, which was translatable to film.”

When Hoberman first visited Binghamton, he wasn’t too enthusiastic about it. He credits Binghamton’s drug use to the depressed atmosphere.

“You had all these kids from New York and the suburbs who just sat down in what, to them, was the middle of no place, with no parents,” he said. “It just seemed like a backwater to me, and sort of exotic for that.”

And indeed, drugs were on everyone’s mind. This was the late ‘60s, and hostility between students and the local Binghamton area ran high. Hoberman said there were very well-publicized drug busts of students. But even with that, he was surprised there weren’t more arrests.

“Drugs were so prevalent on campus, and one of the weird theories was that the reason they were not cracking down harder is that [New York Gov. Nelson] Rockefeller wanted it to be eventually named Rockefeller University,” Hoberman said. “It was a very interesting time. And classes were by no means the most interesting thing going on.”

In 2013, Hoberman published an essay titled “The Cineaste’s Guide to Watching Movies While Stoned” in The Nation. “I’ve heard that the French call one’s late teens and early 20s the ‘age of moviegoing,’” Hoberman wrote. “It certainly was mine; it was also, for me, the age of smoking pot — and for a period of seven or eight years, the two activities were not unrelated.” But in class and at Harpur Film Society screenings, Hoberman remained sober. He said Jacobs thought drugs were unnecessary while watching trippy films anyway.

In line with Binghamton’s drug culture, The Colonial News changed its name to Pipe Dream at the beginning of the 1970 fall semester.

“It was clearly a reference to smoking pot,” Hoberman said. “The Colonial News was a terrible name. Everybody could agree that that was horrible. And of course, in the ’60s, even worse. Like, what are we, colonized people?”

But as the legend goes, Pipe Dream got its name not from pot, but from a quote in Eugene O’Neill’s “The Iceman Cometh”: “To hell with the truth! As the history of the world proves, the truth has no bearing on anything. It’s irrelevant and immaterial, as the lawyers say. The lie of a pipe dream is what gives life to the whole misbegotten mad lot of us, drunk or sober.” Hoberman quickly shot that theory down.

“I’m sure that was brought up,” he said. “Even that would be crazy, because Pipe Dream is used in a completely negative sense in ‘The Iceman Cometh.’ Some literary purveyor or theater person probably just threw that out there.” (Hoberman himself didn’t write for Pipe Dream, but he does remember Tony Kornheiser being “the big writer” on campus.)

Hoberman graduated in 1971 after finishing his thesis film — now housed in the Anthology Film Archives in New York City — for the cinema major and made his way back to the city. Career-wise, he was directionless, living a “bohemian life” in the East Village.

“I drove a cab, I took other jobs like that,” Hoberman said. “I was interested in a fringe theater, this sort of underground theater.”

Hoberman ended up working for the New York City Board of Water Supply for several years, but was laid off when the city neared bankruptcy. He was eligible for unemployment insurance, and floated by on it for a while freelancing for a few zines and alternative papers — Idiolex, High Times, Crawdaddy — as well as the occasional piece in The Village Voice. He adopted the byline “J. Hoberman,” deciding that Jim was too informal and James too stuffy. In the “mid-to-late ‘70s,” Hoberman enrolled at Columbia University for an MFA program for cinema, where he made several more films and continued his freelance work.

At the time, Hoberman was deeply involved in New York City’s underground film scene. Vincent Grenier, a Binghamton University cinema professor, moved to New York from San Francisco in the mid-1970s to join the burgeoning avant-garde community. An important part of that community was a group called The Collective for Living Cinema, which also included now-well-known intellectuals and filmmakers like Judith Shulevitz, John Sloss and Bob Schneider.

“There was one aspect of it which was a little startling,” Grenier said. “It seems that everybody involved in the organization came from Binghamton.”

Grenier quickly recognized that many of those people were Jacobs’ former students, and found Hoberman — as well as Spiegelman — in the scene. At that time, Hoberman was regularly writing about it, and even reviewed some of Grenier’s own films in the Voice.

The Voice hired Hoberman as a full-time film critic in 1983, and he succeeded the legendary Andrew Sarris as the senior critic in 1988. He worked there until 2012, when the paper laid him off.

In those 29 years, Hoberman wrote an astounding body of work. In addition to his regular film criticism, he wrote nine books, including “Vulgar Modernism: Writing on Film and Other Media,” a canonical volume of film criticism; “Bridge of Light: Yiddish Film Between Two Worlds,” inspired by the Yiddish cinema screened for him in Ken Jacobs’ classes; and “Film After Film: (Or, What Became of 21st Century Cinema?),” one of the most important works about cinema in the digital age. He’s also taught, starting at New York University in the mid-1980s and teaching the history of cinema regularly at Cooper Union since 1990, and spoke at BU in the early ‘90s, giving a talk based on “Bridge of Light.”

Like Manny Farber, the film critic who influenced him most, Hoberman writes about complex ideas in a clear and lively way, championing experimental alongside narrative cinema. Farber wrote for Artforum while Hoberman was at BU, and Hoberman picked up on his tendency to neither trash popular movies for being trash nor write esoterically about esoteric films. With every movie he writes about, he brings a rich body of knowledge about film history with him, with a mastery of each director’s oeuvre and where each movie is placed within it.

On campus, he recalls being influenced by some of the ideas that Camille Paglia — the professor, social critic and contemporary of Hoberman at BU — later wrote about on myths and sexual identity. He also remembers being inspired by Spiegelman at Binghamton, even at such a young age.

Shortly before the 2014 NYFF, the magazine Film Comment published Hoberman’s report on the 1968 one. Hoberman ended up using the same trick three times in the next few years without any trouble, and the festival’s lax press standards provided at least one other avenue for great cultural journalism: Andy Warhol began Interview magazine to get press credentials to the NYFF.

Introducing his report, Hoberman reflected on his time as a critic. “For most of the many years I spent at The Village Voice I imagined that my ideal reader was the teenaged Me,” he wrote. “This passionate if puerile moviegoer is that guy.”