When the Maine men’s basketball team played No. 4 Duke on Saturday, victory was improbable. Although a win wasn’t on the horizon, something of greater importance to the Black Bears (2-6) was: the opportunity to make a statement regarding a divisive social issue.

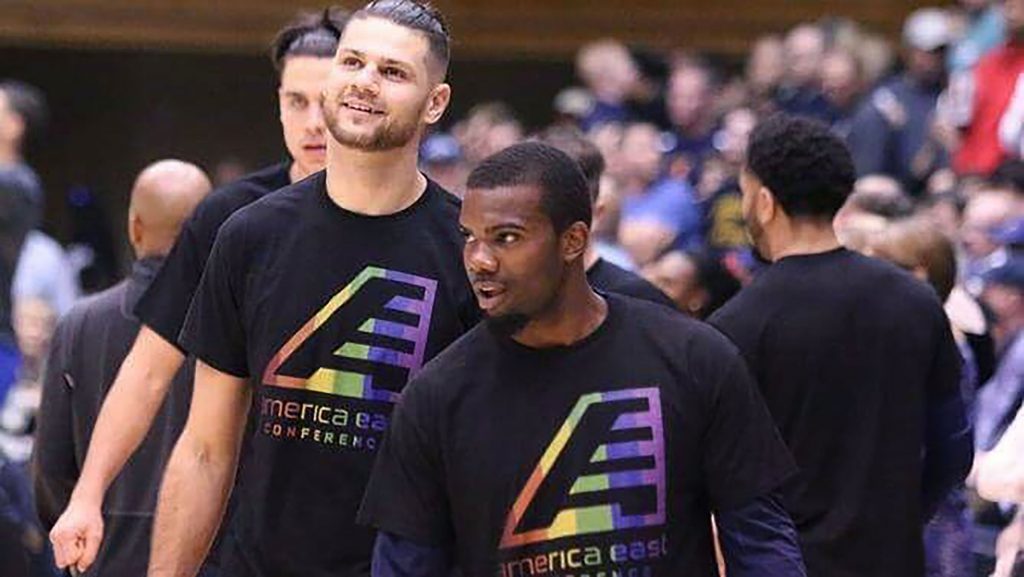

In response to North Carolina’s controversial House Bill 2 law, Maine players donned black T-shirts emblazoned with a rainbow America East (AE) logo. The law, which requires transgender individuals to use public bathrooms that correspond to their sex rather than their gender identity and prevents state anti-discrimination laws from including protections based on sexual orientation and gender identity, was signed by former Gov. Pat McCrory in March.

In reaction to the law, two other AE basketball teams — the Albany men’s and the Vermont women’s — canceled games they had been scheduled to play in the state this season. In July, the Great Danes called off their matchup with Duke in accordance with New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s executive order banning non-essential, publicly funded travel to North Carolina. The following month, the Vermont women’s basketball program also made the decision to cancel its game with UNC.

Maine chose to take quite a different route. The coaching staff, lead by head coach Bob Walsh, decided to use the game as an educational opportunity for its student-athletes and to make Maine’s stance on the discriminatory law clear.

“It’s a learning experience for our guys; they understand what the law is all about and what the issues are on both sides,” Walsh said. “It highlights the inclusion aspect of the America East Conference and what we do here at Maine.”

Prior to their departure for Durham, the Black Bears video-conferenced with three-time U.S. triathlete Chris Mosier, the first transgender athlete to compete for a U.S. national team. Mosier currently serves as the vice president of program development and community relations for the You Can Play Project, the goal of which is “ensuring equality, respect and safety for all athletes, without regard to sexual orientation and/or gender identity.”

During the session, Mosier related his own experiences to the athletes, which include being unable to use the bathroom at a qualifying event for the sprint duathlon national team in North Carolina this past June. He spoke to the players about the actions they could take as male athletes to be allies to the LGBTQ community and counter common misconceptions about transgender individuals.

“I think one of the greatest challenges that LGBTQ athletes face is a lack of understanding,” Mosier said. “People fear what they don’t understand, and so a lot of our work is just creating this visibility, creating a respectful environment and using appropriate language.”

Because Duke is a private university, it is not subject to House Bill 2 and has publicly disavowed it. Before the Blue Devils’ head coach Mike Krzyzewski led the U.S. men’s national team at the Rio Olympics this summer, he termed the law “embarrassing” in an interview with USA TODAY Sports.

Maine’s display of solidarity went further than the physical support accomplished by their conspicuous warm-up attire. Before being routed by Duke, 94-55, on Saturday, the Black Bears met with members of the Duke chapter of Athlete Ally, a nonprofit that encourages student-athletes at the collegiate, professional and Olympic levels to become allies by standing against transphobia and homophobia in their sports communities.

Walsh cited part of Maine’s motivation as its desire to use its influence to bring light to an issue about which it feels strongly.

“It’s important because we have a platform that a lot of people don’t get,” he said. “We do something in a very public forum and we’re given a lot of things. You get all this really important stuff and there’s a responsibility that comes with that.”

The steps taken by Maine fall in line with the AE’s reputation as a progressive conference. In 2012, the AE became the first Division I conference to partner with the You Can Play Project in an effort to change the conversation regarding LGBTQ athletes and their treatment on and off the court. This August, the conference furthered its commitment to acceptance, becoming the first to team up with the LGBT SportSafe Inclusion Program, which aims to “provide an infrastructure for athletic administrators and coaches to support LGBT inclusion in college, high school and professional sports.”

According to Mosier, Maine’s actions and definitive position against discrimination can serve as a paradigm for other institutions that want to further inclusion in the realm of collegiate athletics.

“I really think that other schools could look to the model that Maine has set and replicate theirs if they are in fact going to play games in North Carolina,” he said. “The educational opportunity here and the chance for student-athletes to become better leaders and more engaged citizens is immense.”