African Americans have served in every single war fought by the United States, although they were fighting for American freedoms that they would often be unable to enjoy.

During the time of the Revolutionary War, many African Americans were still slaves and were not permitted to serve in the Continental Army due to fears of an uprising. This ban was eventually lifted by former President George Washington — who initially enforced the ban — after he realized that he needed as many troops as possible.

To entice the slaves to enlist, Washington and other slave masters often gave false promises to grant freedom to all the slaves who served. These slaves, along with free black men, were segregated into all-black units and many were relegated to labor-intensive service positions, rather than fighting in combat. However, the black soldiers’ overall contributions to U.S. forces proved to be crucial, as the United States was able to defeat the British and gain its independence. This outcome likely would not have occurred had those thousands of black men not volunteered.

As time went on, black Americans continued to be segregated in the U.S. armed forces and were still disenfranchised from involvement in some branches, like the U. S. Air Force. Circumstances changed during World War II, as the Tuskegee Airmen became the first African American military aviators in the U.S. armed forces. However, they were still a segregated unit from the rest of the U.S. Air Force. In 1948, after the end of World War II, former President Harry Truman issued Executive Order 9981, which ended segregation in the U.S. armed forces. But this did not mean the end of segregation and mistreatment of blacks — and other people of color — in the U.S. military.

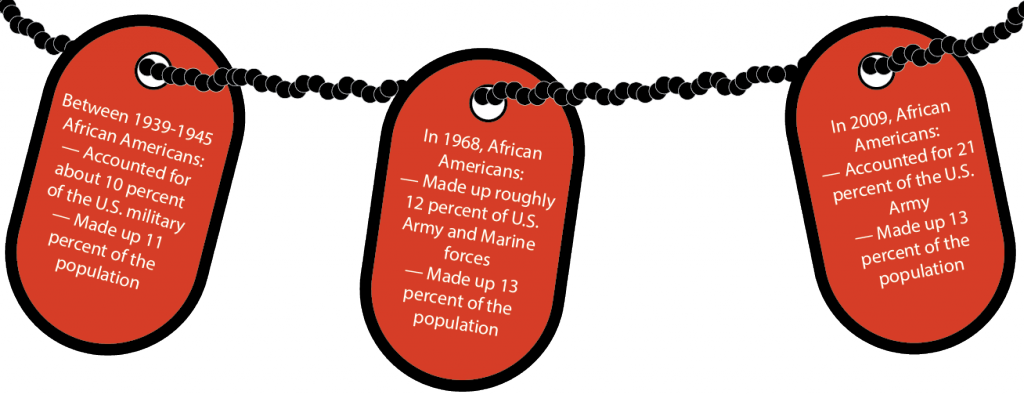

The Vietnam War, fought between the 1950s and the 1970s, brought about more issues for black Americans in the military. According to “The Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War: A Political, Social, and Military History,” in 1968, African American soldiers made up roughly 12 percent of the U.S. Army and Marine forces, yet they accounted for nearly half of the front-line combat unit and made up 25 percent of all Army soldiers killed in action in 1965. These disproportionate statistics show that black lives were deemed invaluable by the Pentagon. They were seen as expendable and were thrown into the front line in droves.

Why, then, do African Americans choose to serve in the U.S. military? The percentage of African Americans serving in the active-duty Army — about 21 percent — is higher than the percentage of African Americans in the entire U.S. population, at about 13 percent, according to 2009 studies from the U.S. Census Bureau and the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel of the U.S. Army. Despite the constant discrimination in and out of the military, many African Americans have been eager to serve a country that has not always served them.

Many black soldiers today come from impoverished communities, with inadequate education and employment opportunities inflicted largely because of the long-standing history of withholding African Americans from the basic rights and opportunities that their white counterparts have had. This economic disparity works in favor of military recruitment. Perhaps many young black individuals have been told to believe that the best way for them to overcome their circumstances is to join the military, which could potentially provide them with many benefits like full tuition coverage for college, low-cost mortgages for purchasing a home and, of course, a job while they are in service.

Perhaps many black Americans are drawn to the military by the promise of career security and a stable paycheck. But is that even guaranteed? Black soldiers were and still are not exempt from the mistreatment that comes with institutional racism and discrimination. How can it be that black soldiers can be expected to fight in the military only to come home and live as second-class citizens?

Wembo Tiapo is a senior majoring in business administration