As students roam the bookstore aisles and search online each semester for the best deals on textbooks, it might come as a surprise that the author of their textbook is sitting at the front of the class.

In addition to teaching, professors at Binghamton University sometimes choose to write, edit and publish their own textbooks to be used in their classes at the University and beyond.

For Victor Skormin, a distinguished service professor in the Watson School of Engineering, writing a textbook for his undergraduate and graduate-level electrical and control engineering classes was not something he originally intended to do, but something he fell into after his 29 years of working at BU.

“After you teach a course more than once, and actually more than 10 times, you have your own ideas of how the material should be organized and what kind of examples you need,” he explained. “Year after year, you look over your notes, and eventually you are shaping your class notes into something that could be published.”

After publishing his two textbooks — Introduction to Automatic Control Volumes 1 and 2 — through Linus Publications in 2010, Skormin has started work on a third volume. He said that he publishes his own books not for personal profit, but because he believes in including information students can reference after the course’s conclusion.

“I know exactly where my graduates will work, and the material I present can be used in their professional tool box; I know what they need and don’t need,” Skormin said. “There is something that they need to demonstrate during [job] interviews, so the book is a way to prepare students for the high-tech environments that they will work in.”

Many professors at BU said they feel similarly to Skormin, including Christopher Bartlette, an assistant professor of music. When there was no music theory review book that Bartlette thought was effective for a graduate music course, he wrote “Graduate Review of Tonal Theory: A Recasting of Common-Practice Harmony, Form, and Counterpoint.” He published his book five years ago through the Oxford University Press.

“Until this book was published, there was no book geared towards these courses,” he said. “The greatest benefit of teaching from my own book is that it is blends easily with my in-class teaching.”

Lucas Daub, a junior majoring in philosophy, politics and law, said that although he enjoys the tailored material, the textbooks align with the course so well that it can be tempting to skip class and rely on the textbook.

“I found that the results of having a teacher who writes their own textbook is that you are more likely to find the lectures verbatim in the textbook, and that’ll encourage students to skip lecture,” he said.

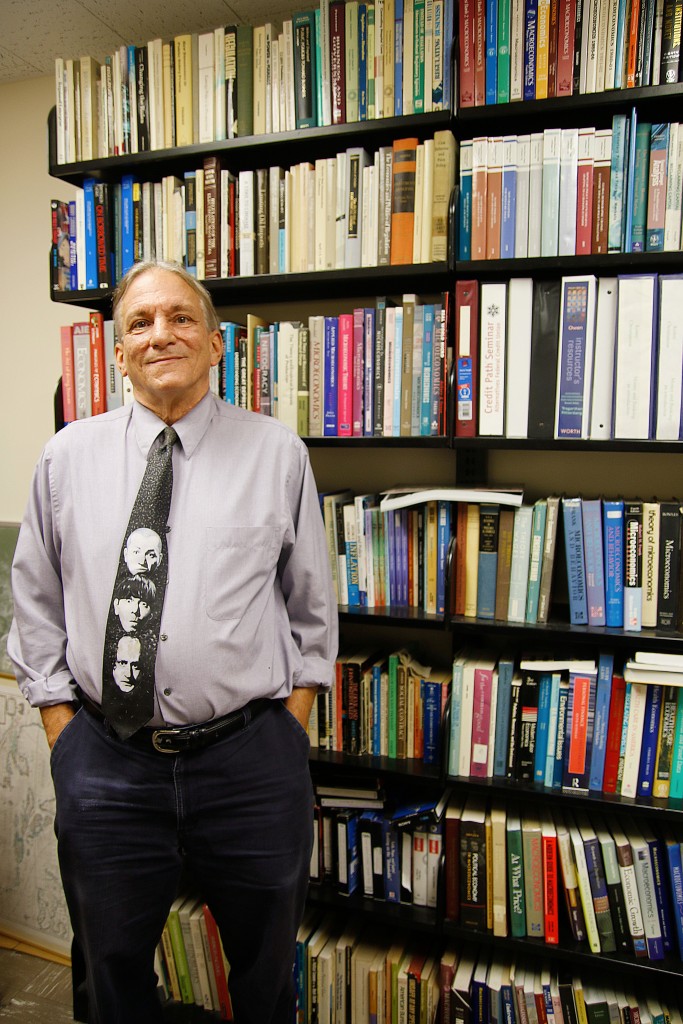

However, Kenneth Christianson, a BU economics professor, had a different motive in writing his own textbook. In 2007, after realizing the bookstore made $50 extra from sales of the original course book, Christianson told his students to boycott until he wrote his own.

“I was sick of the prices that textbook publishers were shoving down student’s throats,” he said. “I knew I could write my own for less money. I also wanted a book that covered both conservative and liberal viewpoints of the economy.”

Jazz Guillet, a junior majoring in English, said that overall, she appreciated her professor’s efforts in making the book more relevant to the class for a good price.

“[Christianson’s] is actually good; he gets to the point,” she said. “A lot of economic textbooks are too far right or too far left, and his is perfectly centered. I’m not bored to death, and I get the information I need.”