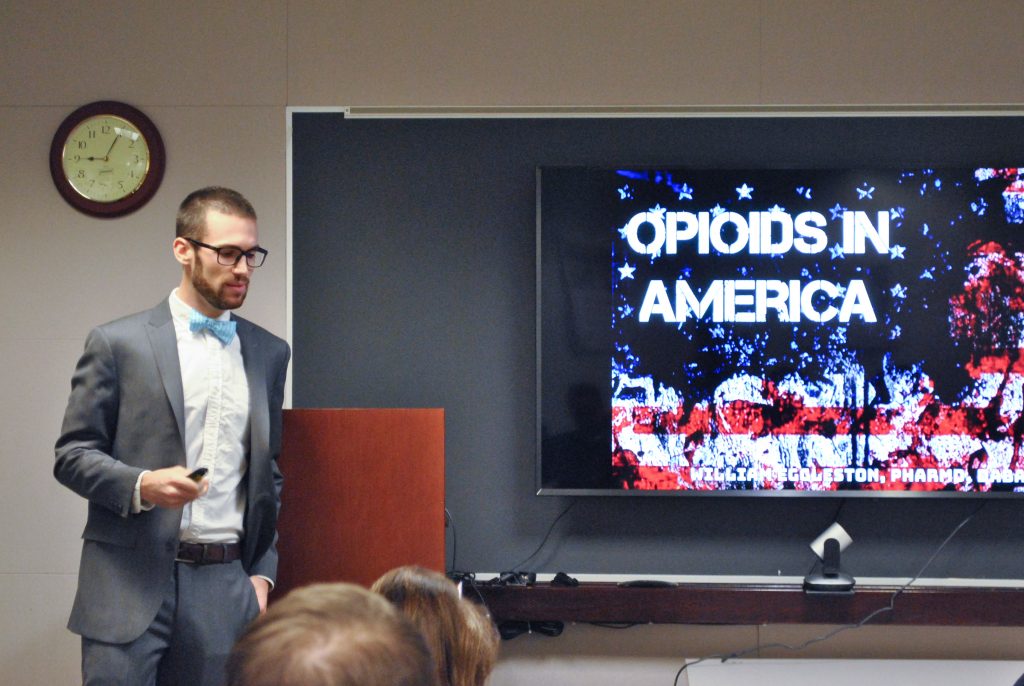

William Eggleston, a clinical toxicologist and an assistant professor at SUNY Upstate Medical University, delivered a seminar on Thursday morning in Academic Building A on the opioid crisis in the United States and possible solutions to the problem.

“We have an epidemic right here in America and we need to do something about this,” Eggleston said. “I don’t think we’re going to solve it right here in this room today, but I think we can start to take some steps … and start to take control of the issue going forward and hopefully prevent loss of life.”

Eggleston graduated from Wilkes University in 2014 with a Ph.D. in pharmacy. After a two-year fellowship studying toxicology with SUNY Upstate Medical Center, he now serves as a full-time clinical toxicologist.

Opium is produced from the poppy plant, and has been used since the 15th century to mitigate pain. Over time, opiates, or drugs derived from opium such as morphine and codeine, began to be used to treat chronic pain in addition to temporary pain. In the 1990s, concerns about addiction and the negative aspects of the prescribed drugs began to emerge.

“Right from the get-go we were left with this balancing act of trying to use and take advantage of the therapeutic benefits of opioids, but also avoid some of those adverse addictive qualities,” Eggleston said.

In recent years, doctors have recognized the addictiveness of opioids and have taken steps to curb addiction. New measures have been recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, like prescription moderating services, pain contracts between doctors and patients to clearly define the goals of their treatment and prescription guidelines. These guidelines are not mandatory, but suggestions for healthcare professionals on how to use opioids correctly in treatment and avoid addiction.

“We are taking the necessary measure to prevent new individuals from suffering from addiction, but we’re not doing anything to help those folks who are already addicted,” Eggleston said.

As prescriptions for opioids decline, patients and addicts are turning to cheaper, more easily accessible alternatives like heroin, which travels to the brain much faster than perception opioids and has a higher risk for addiction.

Addiction, Eggleston said, involves a learned association between taking a drug and the release of dopamine in the brain. A patient cannot recover from addiction after a few days and weeks, but rather it takes months or years for their receptors to return to their original state.

“This is a disease,” Eggleston said. “It’s a chronic disease that people suffer with and we have to reduce that stigma that it is just a series of bad choices.”

Eggleston said that focus should be shifted to help those suffering from addiction to live long enough to seek treatment. He said that needle-exchange programs and the increased availability of Naloxone — a medication used to block opioid receptors during an overdose — are steps in the right direction.

Eggleston’s seminar was part of Binghamton University’s School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences’ hiring process in preparation for its fall 2017 opening. According to Chris Bailey, the administrative assistant for pharmacy practice, candidates for faculty in the new school must complete practice seminars on a topic of their choosing as part of the interviewing process. Candidates have not been announced yet.