More than a billion people around the world identify as Muslim, but just like with other major religions, Islam is not a monolith. Visiting from Morroco, English professor Khalid Bekkaoui looked to break down the significance of just one sect of Islam.

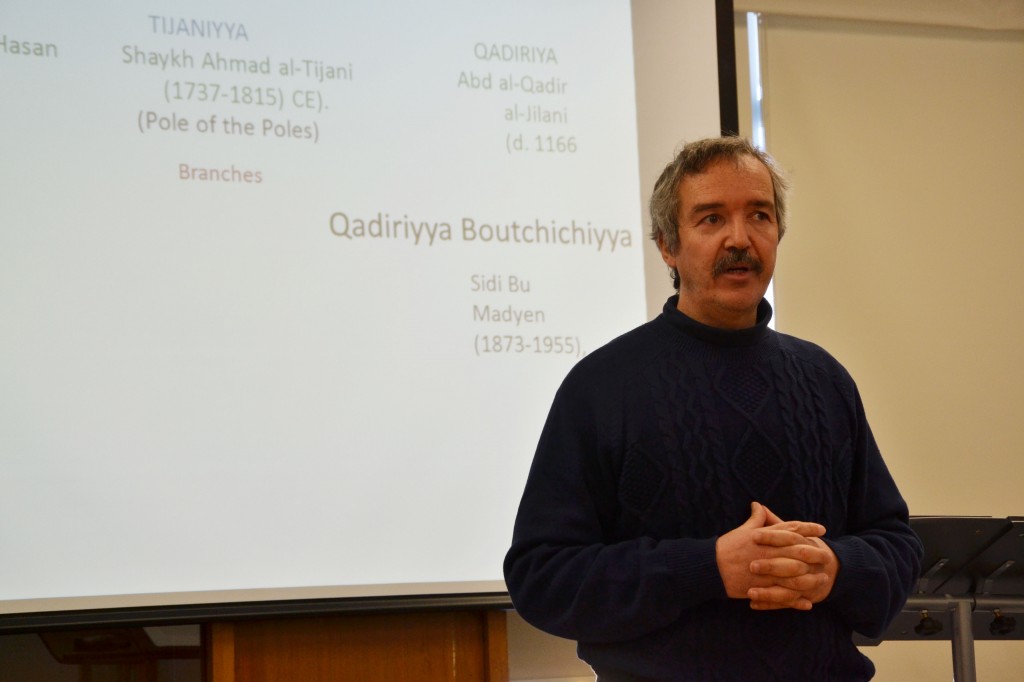

Bekkaoui, a Fulbright scholar at Bridgewater State University and a faculty member at Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University in Fez, spoke Tuesday in the Library North Conference Room about Sufism, a mystical and spiritual sect of Islam.

According to Bekkaoui, Sufism has become increasingly popular in his native country.

“Western media talks about Islam as if it is one homogeneous entity,” Bekkaoui said. “Geographically there are various forms of Islam. Each country has its own, with its own forms and schools.”

Coming from the Arabic word for wool, Bekkaoui said, Sufis believe in a hidden spiritual truth with an emphasis on purification and enlightenment.

According to Bekkaoui, in Morocco there are three major sects in the Sufi movement. An offshoot of one of these branches that has become most popular is called Tariqa Qadiriyya Boutchichiyya. It began in the early 20th century, and by 1990 it had a wide intellectual following in Morocco.

“It’s particularly popular in youth and women because it gives a lot of emphasis on the role of women and encourages learning religion and secular sciences,” Bekkaoui said.

Bekkaoui’s lecture also focused on Sufism within the framework of a globalized society. He described how Sufism has spread through immigration and the Internet, and that people from other backgrounds, such as English and French speakers, are now teaching it as well. According to him, this was uncommon in the history of Islam.

“We are looking at how Islam and Sufism is impacted as it travels outside its natural milieu and how it is appropriated by other people who come from other religious backgrounds,” Bekkaoui said.

One example of how globalization has influenced Sufism is the brotherhood of the Murabitun. It was founded by Scottish-born actor Ian Dallas who converted to Islam in Morocco in the 1930s and now teaches his own school of Sufism in South Africa under the name Shaykh Abdalqadir as-Sufi.

“The Murabitun is a branch of a Sufi, it sees itself as a Sufi order,” Bekkaoui said. “It’s very interesting how he has reinvented a new form of political Islam.”

Although teachings of the Murabitun have many of the same principles and procedures of a typical brotherhood, they specifically believe terrorism and fundamentalism are consequences of poverty and lack of education. To help end terrorism, the group calls for a dismantling of capitalism by boycotting financial institutions and dominant currencies like the dollar.

For Hadassah Head, the Binghamton religion and spirituality project coordinator, that philosophy was particularly intriguing.

“The idea that we need to do something about poverty and income disparity was not a topic that I previously heard being addressed from an Islamic perspective,” Head said.

Although Bekkaoui does not identify as Sufi, his academic interest in it brought him to do a research project with BU’s political science and sociology professor Ricardo Larémont and Africana Studies professor Moulay-Ali Bouanani, who invited Bekkaoui to visit and speak to students.

Kane Sauchuk, a junior triple-majoring in history, political science and philosophy, politics and law, said he found both the lecture and discussion enlightening. Sauchuk said he studied Tunisian and Saudi Arabian religious fundamentalism and its popularity among impoverished young people with limited class mobility.

“It’s fascinating to see Morocco faced with those same problems,” Sauchuk said, “promoting a moderate Sufism as an alternative.”