Just a day after making a televised address announcing he would remain in office until September, embattled Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak resigned Friday and fled the country’s capital of Cairo, leaving the military in charge of the country.

Since gaining control, the military has suspended Egypt’s constitution and dismissed the parliament.

These changes were brought about after protesters gathered in the heart of Cairo, Tahrir Square, and other cities across Egypt, for over two weeks to demand greater economic opportunities and reform of Egypt’s oppressive political system. Thousands of angry protesters demonstrated throughout the night in Tahrir Square after Mubarak’s speech on his intention to retain power. The next morning, Vice President Omar Suleiman announced that Mubarak had left office and turned over authority to the military.

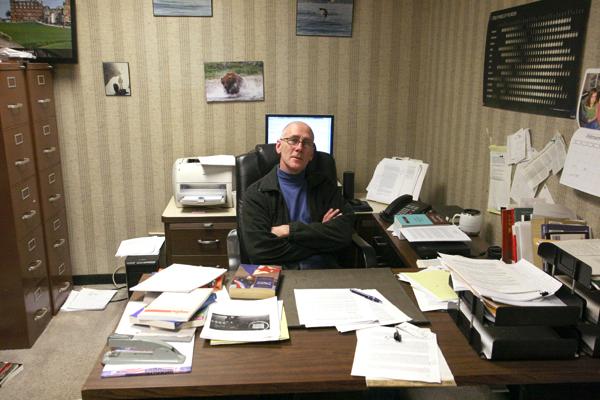

“There was a constant state of emergency which constituted police brutality,” said Ali Mazrui, the Albert Schweitzer professor in the humanities, director of Binghamton University’s Institute of Global Cultural Studies and a renowned African scholar, in reference to Egypt’s Emergency Law which had been in effect since 1967.

“This means security forces could do anything without being prosecuted,” Mazrui said.

Omaima Khan, a senior majoring in anthropology, also decried the lack of civil liberties for Egyptians under Mubarak’s rule. Khan’s mother’s relatives live in Alexandria, Egypt.

“If you spoke out against the government or the police, you disappeared,” Khan said.

As the revolution that eventually toppled Mubarak gained momentum in January and February, the president and those loyal to him tried to suppress media coverage of the protests. Al Jazeera’s news offices were burned by Mubarak supporters, and state security forces jailed journalists and banned filming in Tahrir Square by international media.

On Jan. 28, the Egyptian government cut off text messaging and Internet access in the entire country.

“They were hoping, like most autocratic leaders, to diffuse the protests,” said Patrick Regan, a political science professor who specializes in the study of violent armed conflict and its resolution. “In this day and age, those are the primary vehicles.”

Mazrui called the Internet shutdown a form of technological censorship aimed to stop the Egyptian people from organizing.

“It misfired because people went to Tahrir Square and contributed to the size of the demonstrations,” he said.

Khan’s aunt and cousin are doctors who aided injured protesters in Egyptian hospitals during the massive rallies. She said she was not surprised by the resilience of the Egyptian people.

“Egyptians are a stubborn people. I knew without a doubt they weren’t going to leave the square until [Mubarak] left,” she said.

When protesters’ demands were not met after several days, labor unions carried out nation-wide strikes. The two weeks of demonstrations cost Egypt $1.5 billion in lost tourism revenue alone, according to a report from Bloomberg.

Mazrui, who visited Egypt last year, said he believed that pressure from the international community — including the United States, which, according to the State Department, contributes more than $1.3 billion to the Egyptian military — was a factor in Mubarak’s resignation.

The Egyptian military is currently ruling the country until new elections are held, which are scheduled for September. But according to Mazrui, fully free and fair elections are more likely at the very start of a regime change.

“As an African, I know success is easier than subsequent elections. They have to try hard so that it does not go to corruption and rigging,” Mazrui said.

Regan was not convinced that real democracy is possible for Egypt.

“The people’s rights can be secured without what we think is a free and fair election,” he said.

Widespread government corruption was a major spark to the unrest in Egypt. Mubarak had amassed a fortune estimated to be in the billions of dollars stemming from business contracts, a practice that started during his time as an Air Force officer.

Khan said she thought many outside Egypt did not understand how powerful he was in the country.

“He stole a ton of money,” Khan said.

Corruption in Egypt is not just limited to the government sector. According to a report in The New York Times, the Egyptian military elite run 40 percent of the country’s commercial enterprises, including gas companies and hotel chains.

“Military control of resource is certainly not healthy in terms of long-run economic development,” said Wei Xiao, an economics professor at BU. “What Egypt needs now is a smooth transition both politically and economically.”

Xiao said Mubarak stepping down had positive effects on the global markets, which in the past weeks were shaky because of rising oil prices and a fear of a trade freeze at the Suez Canal amidst Egyptian labor strikes.

“Not only did the S&P 500 and Dow Jones gain, but emerging market indices also edged up after at least one week of sliding downward. Oil prices also dropped,” Xiao said. “However, I believe investors are still cautious about the negative impact of Egypt’s peaceful revolution. It is still likely this event might trigger similar unrest in other Middle Eastern countries such as Libya, Syria and Yemen.”

The protests descended into violence at times in the past weeks.

Police vans plowed through crowds at high speeds in attempts to clear the streets. Live ammunition was fired on peaceful protesters and an Al Jazeera reporter tweeted that hospitals were being ordered not to record injuries by bullets. Looters of shops and museums caught by mobs of protesters were found to be carrying government guns and identification. It remains unclear if provocateurs will ever be prosecuted.

“In Egypt we’re lucky to have only 300 people dead,” Mazrui said. “So much of the violence came from pro-government forces.”

A concern for many observers has been what would happen if Egypt’s largest opposition group, the Muslim Brotherhood, gained control. The Brotherhood says nonviolence is the organization’s official policy, but has also publicly supported suicide bombers who targeted Israelis and U.S. troops in Iraq and said it would end Egypt’s peace treaty with Israel, according to a report in The New York Times.

“I don’t think the Muslim Brotherhood can get that kind of power,” Khan said. “I think the word Muslim incites fear and concern where it’s not needed. This was not a religious issue. It was for the people, by the people. I’m very proud of Egypt.”