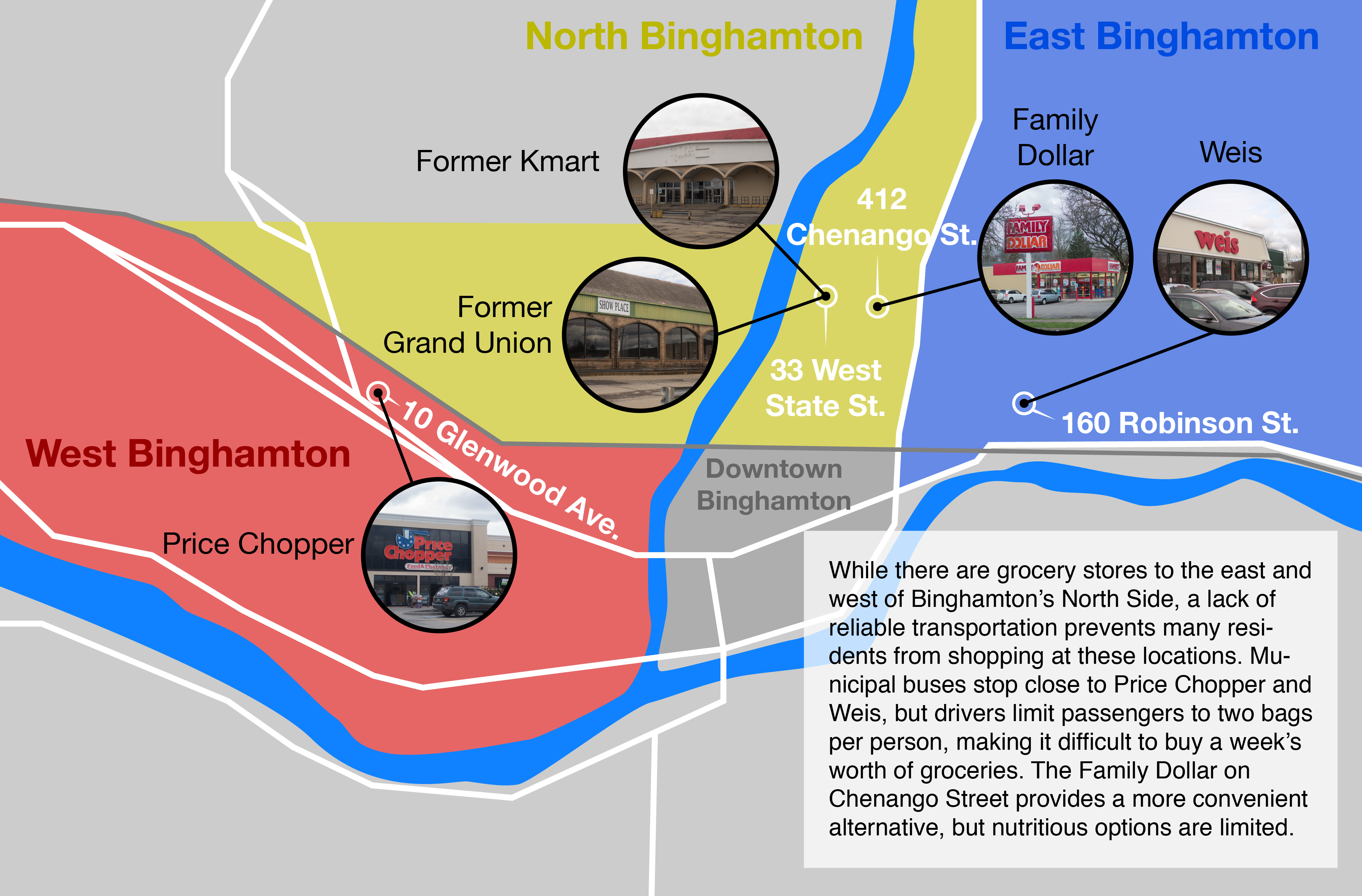

When the last full-service grocery store on Binghamton’s North Side closed in 1996, community members thought it would be just a short time before the city found a for-profit chain to replace the former Grand Union. Twenty-two years later, it is still difficult for the residents of the neighborhood to buy affordable or good quality fresh food, qualifying the area as a food desert.

Now, community members are taking measures to open a local grocery into their own hands.

David Currie has worked under the Binghamton Regional Sustainability Coalition since 2010 to expedite change in the area. He has taken the lead in introducing a concept that may seem out-of-the-box to may Binghamtonians: a food cooperative, or co-op.

“We all feel very strongly that it will succeed and it will succeed as a co-op,” Currie said. “The co-op structure is ‘one person, one share’ and that membership, or that share, gives you a sense of loyalty to the institution. You buy into the concept, and that means that you’ll also shop there.”

Many Hands Food Co-op was created by Currie while he served as the executive director of the Binghamton Regional Sustainability Coalition. While the co-op has not yet been built, a community of supporters has formed around the mission of Many Hands Food Co-op, one of the coalition’s many community-based projects.

According to Feeding America, 41.2 million Americans live in food-insecure households, meaning they lack reliable access to a sufficient quantity of affordable, nutritious food. In Broome County, the food insecurity rate ranges from 14.5 percent to 17 percent. The county exceeds the national average, which estimates only 12 percent of households are food insecure across the United States.

Over the many years since the closing of the neighborhood’s last grocery store, the face of the North Side has changed significantly. Roughly 53 percent of households on the North Side are families, many of which have lived in the neighborhood for generations. But in recent years, the community population has expanded to include immigrant families moving to the Binghamton area, attracted by the low property values.

Conrad Taylor, ‘17, serves as the city councilman for the 4th District, which encompasses the North Side, and sits on the Many Hands Food Co-op steering committee. He said rallying behind positive projects like the food co-op is necessary in order for the neighborhood to move forward economically.

But, like Currie said, instituting community change is anything but a straight line. Food deserts are often indicative of other flights of capital in the area, which adds a layer of complexity to the issue.

Since food deserts tend to be in low-income neighborhoods, many symptoms of the problem arise. Without access to a supermarket, people frequently spend more money on cheap, highly processed foods, leading to increased rates of obesity, diabetes and heart disease in low-income communities and areas struggling with food insecurity.

“With poverty and food insecurity, you have a lack of accessibility, so feeding your family, which is already hard enough, becomes that much harder,” said Eamon Ross, a member of the food co-op’s steering committee and a senior majoring in political science.

While a food co-op serves as one option for the community, residents like Nick Plavae, who has lived on the North Side for six years, are happy with any accessible grocery option in the neighborhood.

“There’s nothing to eat,” Plavae said. “It would be nice if there was somewhere to fill your belly close by. It’s very frustrating.”

Since the close of the Grand Union, a number of projects have been proposed, but all have fallen through.

In 2009, a Save-a-Lot franchise was slated to open in the former Big Lots Plaza at 435 State St., but when another location owned by the franchiser started to decline financially, the Binghamton area development was pulled.

That same year, the North Side’s closest grocer, a Giant located at 56 Main St. on the West Side, closed after Weis Markets acquired all Giant locations.

It was then that Many Hands Food Co-op was conceived, hosting its first planning meeting in early 2010. At the same time, Lea Webb, then serving as city councilwoman for the 4th District, was working to address food insecurity in the community under the North Side Grocery Project.

According to Currie, the two projects first partnered in earnest around 2013. That spring, Many Hands Food Co-op became incorporated. Currie, Webb and a team of volunteers put together a business plan and feasibility study and presented it to the Binghamton Local Development Corporation.

In November 2013, Mayor Rich David took office, bringing along his own campaign promises to find a grocery store for the North Side. He formed a committee, which took shape as a continuation of Webb’s North Side Grocery Project, and looked for a private operator for the property at 435 State St.

All signs were optimistic when, in July 2014, two developers proposed Grocery City Market, part of a $3.5 million development called West State Street Plaza. The developers, one of which had worked on the original developments of Big Lots Plaza, planned to partially demolish and rebuild the space, which was somewhat structurally unsound after being built on a garbage dump.

The damage to the building, however, turned out to be greater than the developers originally thought, and according to city of Binghamton Deputy Mayor Jared Kraham, they were not able to work through the structural problems of the building.

The promise of a grocery store near actualization put the Many Hands Food Co-op into hibernation, Currie said, as it wouldn’t be as necessary in the neighborhood. The excitement for the project died down, and Currie and his colleagues stopped seeking out prospective funding for the project, as it couldn’t compete with a chain-operated grocery store.