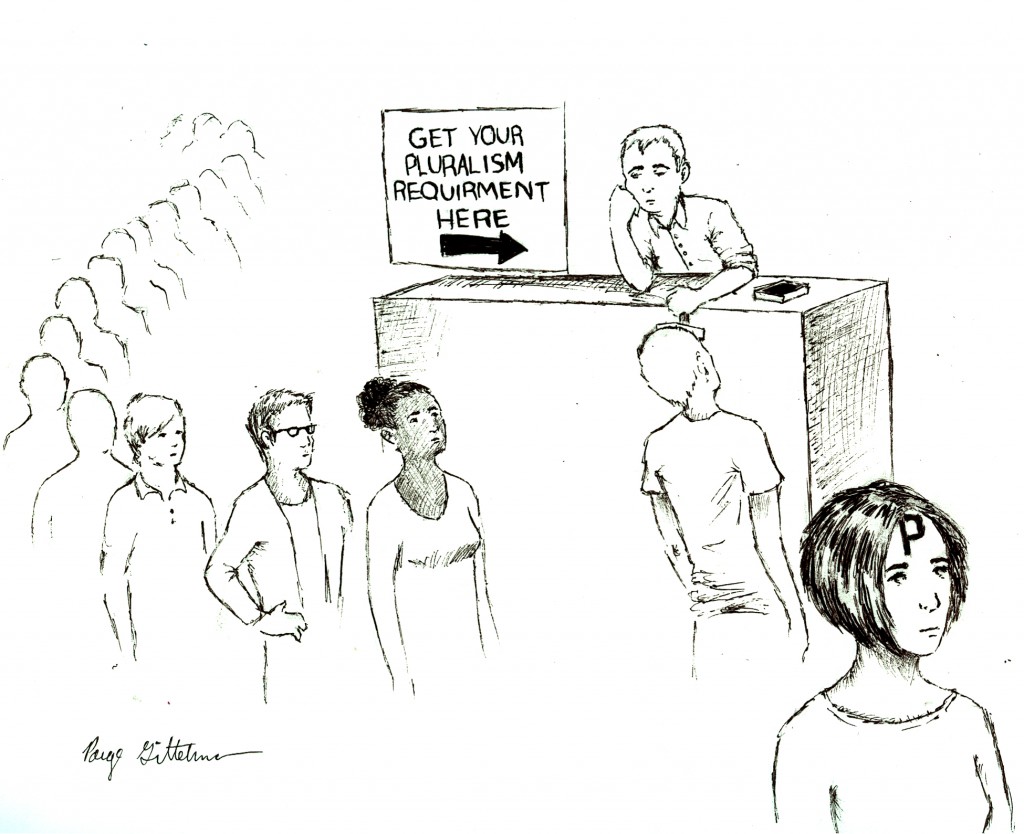

Part of Binghamton University’s role to cultivate a learned student body is to assign general education requirements. But without a careful eye, the original purpose of those requirements can be lost. On Tuesday, the University announced the first changes to the pluralism (P) GenEd requirement since its creation in 1995, curbing a trend in which students could fulfill the requirement by merely learning the basics of American history in high school and encouraging a way to learn more about the issues relevant to the ones students face today. But the changes aren’t enough.

To reform the curriculum, the University must decide on a clear definition of “contemporary” issues. In a past editorial, we’ve argued that the pluralism credit should exist to teach students about oppressive power structures, the experiences of marginalized groups and institutionalized oppression. A solid understanding of these issues is invaluable. Unfortunately, not all of the current class options that fulfill the “P” credit provide students with this foundational understanding. The requirement should then be redefined to focus on these core issues. Any class, whether it be on gender studies or indigenous peoples, must open students’ eyes to the oppressive structures that underly society in ways we may not discover on our own outside of the classroom.

Though a complete overhaul of the requirement will obviously involve the addition of new courses, old ones will also have to get the boot. Courses such as “Introduction to American Politics” should count toward a political science degree, but that curriculum should not fulfill a “P” credit. An understanding of our basic governmental structure doesn’t provide students with any degree of cultural competency or understanding.

The same logic applies to Advanced Placement credits. The effort taken by some high school students through AP courses should be recognized at the university level, but learning about checks and balances in AP Government isn’t quite the same as studying “three or more cultural groups in the United States in terms of their specific experiences,” which is the definition of the pluralism requirement given by the University. Success in an advanced high school course should satisfy a different requirement, such as social sciences, since there is no reason a student should place out of a chance to increase their cultural competency. It is necessary to learn about these things in a college environment where students are pushed to think more critically than they were in high school.

We also want to see a standard of uniformity across the various sections of pluralism courses. When multiple professors conduct these courses, they may teach substantially different material for the same course. Students may encounter vastly different material and receive credit for allegedly the same requirement. We find this problematic. Obviously, faculty have different areas of specialization as well as distinct viewpoints that contribute to the manner in which they instruct their courses, and of course this enhances the university experience. Specific course loads should follow basic guidelines to ensure an academic outcome shared by every student at the conclusion of each semester. Professors are entitled to their own individual styles, as long as essential subjects are covered within a semester.

Pluralism shouldn’t just be a box that we all check in order to graduate. As a university community, we are facing some of the hardest truths about diversity and marginalization right now. It’s time to turn this requirement into something meaningful and productive.