One Rutgers University professor believes punitive drug policies need to get with the times.

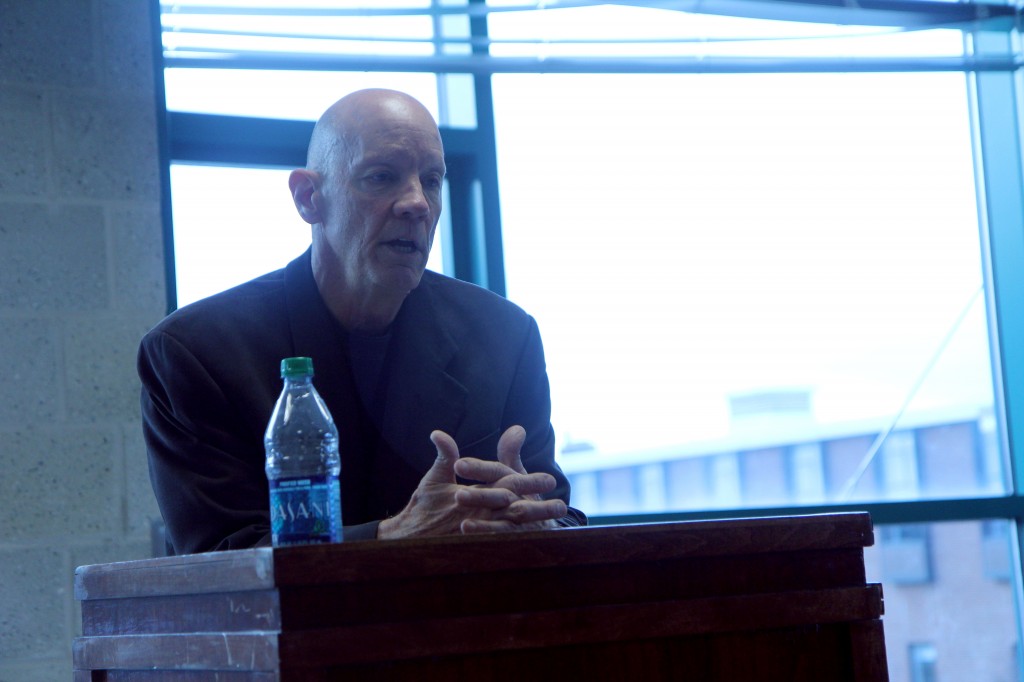

Douglas Husak, a professor of philosophy at Rutgers University, explored the decriminalization of drugs and the current status of U.S. drug laws in his talk Thursday, “Why Our Punitive Drug Policy Persists.”

According to Husak, since the peak of drug use in the United States in 1979 — when 50 percent of high school seniors were using drugs weekly — drug laws have remained punitive and have even become harsher.

This, he said, contrasts predictions of the time that drug policies would become more tolerant, as those who used drugs assumed political office and reformed drug laws.

Husak said one reason this didn’t happen is that as drug users become parents, their perspective change as they consider the dangers drugs could pose to their children.

Husak said finding philosophers who support the current state of drug laws is almost impossible.

“It’s really hard to find a knowledgeable, philosophically sophisticated spokesperson who supports anything like the status quo in drug policy,” Husak said.

He added that the war on drugs was once considered necessary in order to win the war on crime, but that over the past 20 years, crime in New York City has decreased to an all-time low, while drug use has remained steady.

Husak said harsh anti-drug policies can make adolescents more inclined to try drugs in the first place.

Charles Goodman, an associate professor of philosophy and Asian and Asian-American studies, said he agreed with many of Husak’s beliefs.

“I think that our laws, especially in the case of marijuana and probably in the case of other drugs as well, are seriously unjust, and not worth what they cost,” Goodman said. “In order to get a policy that will not cause all this needless suffering, people need to develop more empathy and compassion for those in poor, high-crime communities.”

One claim that Husak made, however, drew opposition from some audience members. He said that after talking to high-ranking officials in New York state’s criminal justice system, most were searching for drugs in low-income, high-crime neighborhoods populated mainly by minorities.

He went on to say that while many might call this racism, talking to the officials led him to believe that drug busts are used as a pretext for solving serious crimes, such as murders and rapes, by getting information from those they arrest as well as having their information in the database.

One audience member asked why, if racism is not a factor, it is more likely for an African-American standing on a corner in Harlem to be frisked rather than a white man on Wall Street.

In response, Husak told the story of one meeting he had with Cyrus Vance, the district attorney of New York, where he brought up the same issue. According to Husak, Vance was aware of the alleged drug use on Wall Street, but said that neighborhood and those like it are not heavily crime-laden places, and that police simply “go where the crime is.”

Although Husak believed that racism wasn’t the driving factor behind drug policy and crime prevention, he did admit that he observed an over-inclusive tendency for the penal system to crack down on minorities, saying that minorities were more likely to be arrested, prosecuted and harshly punished for their crimes.

Stephanie Izquieta, founder of the Binghamton University chapter of Students for Sensible Drug Policy and a junior majoring in philosophy, politics and law, said she was shocked by a few of Husak’s opinions.

“I was surprised that he didn’t really feel that drug persecution or criminalization was racist in and of itself,” Izquieta said. “The movement does kind of say that … it has racist aspects.”

Husak has published eight books and over 100 articles on the subject of the philosophy of law. He is currently editor-in-chief of Law and Philosophy as well as Criminal Law and Philosophy.

Thursday’s talk was a part of the philosophy, politics and law department’s Visiting Scholar series.