This spring, students in HIST 380D: Women in the Modern U.S., had the opportunity to speak to an unlikely visitor.

Leigh Ann Wheeler, a professor of history at Binghamton University, has spent years researching Anne Moody, an African American author known for her activism amid the Civil Rights movement, and her widely shared autobiography, “Coming of Age in Mississippi.” In 2018, Wheeler learned she was not alone in her research, crossing paths with Glen Conley, a prisoner at Mississippi’s Wilkinson County Correctional Facility (WCCF), who she would eventually invite to speak with her class.

Conley, who has spent over two dozen years incarcerated and is currently serving a life sentence without parole, was researching Moody as part of the WCCF Anne Moody History Project, an initiative which allows prisoners to learn about the activist through a book group. When teaching a class on Moody in 2017, Wheeler was introduced to the program after stumbling upon a website created by a chaplain at WCCF.

Wheeler soon became interested, donating 50 books to be used in the initiative, which prisoners then used for discussions, readings and creative works projects. Through the program, Wheeler became acquainted with Conley, who had asked her to write a foreword for a self-published book of poetry he was writing on Moody.

“So [Conley’s] friend — his name is David — David sent me the poems and I was really moved,” Wheeler said. “I was moved by his insight on Moody, and I agreed to do it. So I wrote the foreword, and David sent it to [Conley], and he loved it.”

Wheeler’s relationship with Conley would grow stronger over the years, as both Wheeler and Conley would share their research with each other. In 2021, Wheeler invited Conley to make a virtual appearance at the Western Association of Women Historians Conference in California, in which Conley presented his research paper on the factors behind Moody’s advocacy.

For Conley, the event was not only a place to share his ideas, but it was also a source of validation, as Conley was the first Mississippi inmate to present at an academic conference.

“It also meant a lot to me that people outside, particularly educated people, historians, academicians [and] people involved in pedagogy, were interested in hearing what someone inside had to say, because there are so many stereotypes that go along with an incarcerated person,” Conley said.

Conley’s research focused on the impacts of white people in Moody’s life, and the extent to which they served as inspiration for her advocacy. As Conley described, his thesis was not an ordinary one found in discussions of Moody.

“You know, many times in doing research, people only report part of the story, they’ll basically put their own angle into it,” Conley said. “For example, they’ll show, ‘This person is pro-Black,’ but they’ll frame it as, ‘This person is against the whites.’ And I found in Anne Moody’s case that that was not true.”

To Conley, Moody’s surroundings were far more nuanced. Conley described how Moody’s mother, along with other close family members, would urge her to limit her advocacy out of fear. Instead, Conley said Moody gained some motivation from the white people she had worked for, with some even teaching her how to read.

Conley said his research allowed him to make parallels with contemporary movements, including the Black Lives Matter movement, drawing him to the conclusion that change is most easily brought upon by working together.

“I concluded that it’s only when we become unified in our approach to solving the problems of civil rights, and stop pointing fingers at each other, that we’ll come up with a solution that works for everybody,” Conley said. “And [then] we can begin to make progress.”

Back in BU, as the COVID-19 pandemic continued to take hold, Wheeler said she often found herself thinking of creative ways to bring speakers to her students, including using Zoom to host authors for her graduate seminar. After seeing the impact Conley’s participation in the panel had on him, Wheeler soon decided to invite Conley to speak with her undergraduate history course.

“It was clear to me that the conference experience was really incredible for him in ways that I can’t fully appreciate, because I don’t know what it’s like to be where he’s been,” Wheeler said. “And so, I guess I was interested in ways to recreate something like that for him.”

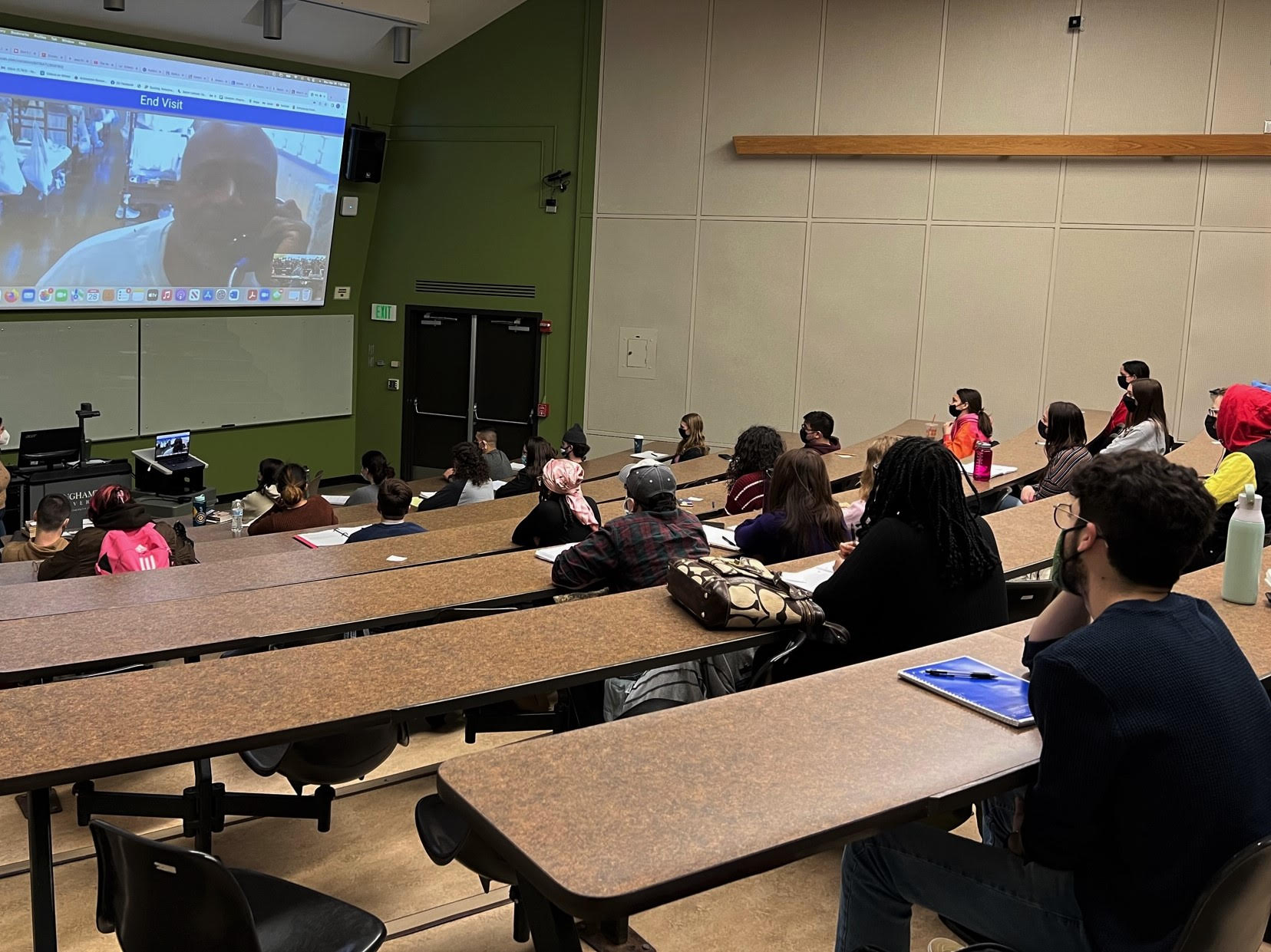

Wheeler said she was initially nervous of how her students would perceive Conley, as the event was the first of its kind she had held in her class. When the call began, with Conley’s video on a screen at the end of the lecture hall room — and the call split into three, paid 15-minute segments — Wheeler was pleasantly surprised by her students’ reactions.

“I thought it was incredibly powerful,” Wheeler said. “It was clear the students were moved. Some students, who said they weren’t going to participate and weren’t going to ask questions, actually got up from the back row and walked down to the front and sat down in the chair in front of the camera, took off their mask and asked him questions.”

Students were able to submit questions to Conley verbally or in written form.

Students were able to submit questions to Conley verbally or in written form.Students in the class were able to either ask questions verbally to Conley, or to write their questions for a teaching assistant (TA) to read.

One student attendee, Sarah Grace-Willemite, a sophomore majoring in economics, said she was impressed with Conley’s research and efforts amid the restrictions he faced in prison. In addition to his academic research, Conley had also earned a Bachelor of Arts in Christian Ministry from the New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary while incarcerated.

“So many offenders lose contact with the ones they love because they begin to believe the conviction or because the time spent inside is such a complication in their relationship, but [Conley] still has the family that he left when he went inside,” Grace-Willemite wrote in an email. “He has reached out and tried to be a part of multiple prison reform projects and organizations but it is incredibly difficult to even get access to the internet while in prison and he is constantly monitored.”

In a fundraising campaign online, Wheeler had called for support in appealing what she described as Conley’s false incarceration, noting his “exemplary” institutional record over 25 years, which includes receiving an award from a warden in 2019 after providing first aid to a collapsed correctional officer. In addition, Wheeler had noted what she described as inconsistencies in the case, including changing accounts from witnesses, a lack of communication from Conley’s lawyers and the testimony of a controversial pathologist lacking board certification.

Grace-Willemite said her experience with the event allowed her to better understand the perspectives of those incarcerated.

“The whole class loved hearing his story and the details about what it’s really like being incarcerated, especially in the South,” Grace-Willemite wrote. “I truly think his personal experiences he shared with us brought so much first-person perspective to what incarceration is like within America.”

Noelle Dutch, a sophomore majoring in political science, said she was touched by Conley’s responses.

“Any time a classmate asked a question, he was sure to find where they were seated through the video call, actively listen and repeat back our names before he answered a question,” Dutch wrote in an email. “It meant a lot to him to interact with people on the outside, particularly a large group of young scholars who were interested in his work.”

Erin Heard, an adjunct lecturer in geography, had also attended the class, as her own class took place in the same room after Wheeler’s. While she hadn’t prepared questions for the event, Heard said she enjoyed attending.

“Her class and specialty are very different from mine, and I am always excited to learn from others so I gratefully accepted her invitation,” Heard wrote in an email. “I quickly Googled the guest speaker to get some info on him before the call began. There was some information on him, a little on his conviction and then on his work while incarcerated. It was a very interesting Google search.

Heard said she found the event and questions asked by the students intriguing, particularly the emphasis on Conley’s academic research.

“The questions mostly focused on his research, what prompted him to begin his work and the difficulties in gaining access to research materials behind bars,” Heard wrote. “I would say that this was probably the most surprising to me. There is a lot of red tape involved in even academic research, which could be seen as part of rehabilitation and an asset to the individual and the institution.”

Beyond his experiences with Wheeler and research regarding Moody, Conley said he particularly drew inspiration from Anthony Ray Hinton, an Alabama resident who was on death row for 28 years under a wrongful conviction. Hinton had spoken with BU students through a virtual event in 2020. Conley said he had based poetry in his book off of Hinton’s story, including the book’s final poem, titled “The sun does shine.”

Conley said that the event in Wheeler’s classroom, like his experiences in the panel conference, allowed him to form connections that may bring about change.

“Many on the outside are blinded by the stigma that society at large puts on incarcerated persons,” Conley said. “It’s very beneficial to me in that regard. Not only that, I feel that this opens up many possibilities. One possibility [is] it may begin to help free members of society, take a different view, a different approach toward people on the inside. It may help them to realize that people on the inside have potential.”